The development of high-quality affordable housing on Beacon Hill has historically been a priority for residents. Prominent figures like John Bok and Tad Stahl were directly involved in the acquisition and development of properties that might otherwise have fallen into the hands of luxury condo developers. An April 16, 2020 article in the Beacon Hill Times details some of this history. A careful review of records provides further insight.

According to public data from HUD, there are several actively federally subsidized housing properties in Beacon Hill. These data, along with details of their development, are summarized in the table below.

| Address | Name | Year Redone | Developer | Subsidized Units |

| 45 Myrtle St | Bowdoin School | 1975 | Wingate Development Corp | 16x 1BR, 10x 2BR |

| 250 Cambridge St | Anderson Park | 1976 | Bob Kuehn | 32x 1BR, 30x 2BR, 2x 3BR |

| 56 Joy St | Joy St Residence | 1993 | Rogerson | 10x 1BR, 4x 2BR | 19 Myrtle St | Beacon House | 1983 | Rogerson | 85x Studio |

A careful examination of each property shows how neighborhood involvement, experienced developers, and high standards are all essential parts of Beacon Hill's history of successfully developing affordable housing.

There is also a notable counterexample. The only affordable housing with SROs without bathrooms or kitchens is Bowdoin Manor at 37-41 Bowdoin St, which was not developed with community involvement. The result has been a source of crime and problems for the neighborhood. The property, which has been poorly managed (see reports of rats in bedsheets and drug sales in units in a 2023 Globe article, for which no landlord was available for comment), appears to have been dropped by HUD as of 2023 according to publicly available data from their multi-family database (listed above) and from the Continuum of Care competitive ranking. Neighbors who are front-line workers also report that tenants were all stricken with COVID-19 at the same time during the pandemic, likely due to unhygienic conditions in shared bathrooms and kitchens.

Built in 1899-1900 in restrained but elegant Colonial Revival style, Beacon

Chambers was one of the first commissions for noted Winchester architect

Herbert

Dudley Hale. From the outset, the building was a 350-room

single-room-occupancy (SRO) hotel for men with shared bathrooms and facilities,

and it operated this way for 80 years until a six-alarm fire displaced the

tenants on October 13, 1980.

According to a November 15, 1980 Globe article, When it became clear that repairing the building and bringing it back up to code would be time-consuming and expensive, the owner (Thomas F. Keating of Beacon Chambers Corp.) of the rooming house announced intentions to sell the building for revelopment as luxury condos.

However, Community organizations like the Back Bay/Beacon Hill Tenants' Union and The Beacon Hill Civic Association rallied around the tenants, many of whom were elderly and poor, and for whom Beacon Chambers had provided a sense of belonging and support that they would not have found at the YMCA or a smaller building. With the help of Greater Boston Legal Services, they brought a class-action suit against the owner demanding that the building be repaired and the tenants allowed to return.

In a landmark ruling, Judge E. George Daher sided in favor of the tenants. According to a November 26, 1983 editorial in the Globe, the support of the community for the effort was a crucial deciding factor. A July 25, 1982 article describes how the BHCA's support helped bring on Rogerson, who had operated elderly housing in Jamaica Plain since 1890, and who were able to obtain federal subsidies and 121A tax agreements to make 83 studio units affordable for seniors, and 19 units available to visitors of long-term patients at MGH who could not afford hotels.

Rogerson continues to operate the property to this day, offering affordable housing for seniors in high-quality studio apartments with private bathrooms and kitchens. A list of other amenities is listed along with the details of their award-winning renovation completed in 2001. The building is well-known to Hancock Street neighbors since it also serves the public as a polling center for Ward 3, District 17.

Designed by Edmund March Wheelwright and built in 1896, the old Bowdoin School building at 45 Myrtle St was closed to students in 1936 and was used for administrative staff until the 1970s. As with many redundant city properties at the time, there was interest in developing the building into luxury condominiums in the 1970s.

However, when the Beacon Hill Civic Association caught wind of this, it intervened to stop the city from selling the building to luxury developers. Instead, according to an August 17, 1975 Boston Globe report, the BHCA “negotiated with the city's Public Facilities Department” to make the building available for affordable housing.

They engaged Gerald Schuster of Wingate Development Corp, who filed paperwork in July of 1975 to create the Bowdoin School Associates Limited Partnership. This certificate of formation explains how the project was financed via the Massachusetts Housing Finance Authority (MHFA, now known as MassHousing). It was responsible then, as now, for offering funding for affordable housing projects in the form of loans and mortgage guarantees.

Another Globe article dated Feb 13, 1977 described how Schuster and

Wingate had recently secured funding for several affordable housing projects

despite an MHFA mortgage lending freeze due to deteriorating market conditions

for municipal bonds. Under

Section 221(d)(4)

the federal government provides favorable insurance for mortgage loans to

encourage the development of multifamily properties with single-room or studio

units. By combining these with rental subsidies under

Section

8, which had recently been authorized by Congress in 1974, it was possible

to finance the rehabilitation of the building into high-quality housing with

subsidized rent for low-income tenants.

In 1971, with the demolition of the West End (a neighborhood of which the so-called “North Slope” and nearby streets were once considered a part) still fresh in everyone's mind, a group of neighbors and allies organized the Cambridge Street Community Development Corporation. Their Articles of Organization lists 11 directors, including John Bok of Pinckney St, Frederick “Tad” Stahl of Hancock St, Lawrence Coolidge and John Howe of Mt Vernon St, and Anne Witherby of Chestnut St. Their stated purpose was to further the development of Cambridge St, to create a plan for that development, and to acquire and rehabilitate properties on that street.

According to a February 25, 1979 Boston Globe article, their plan included a general aim to keep hospital expansion on the north side of Cambridge St, and to “strengthen the other side for residential and complementary uses.” This led them to champion the decommissioning of the old Charles Street Jail (which would later be redeveloped as the Liberty Hotel), but a more immediate focus was developing housing on the south side of Cambridge St.

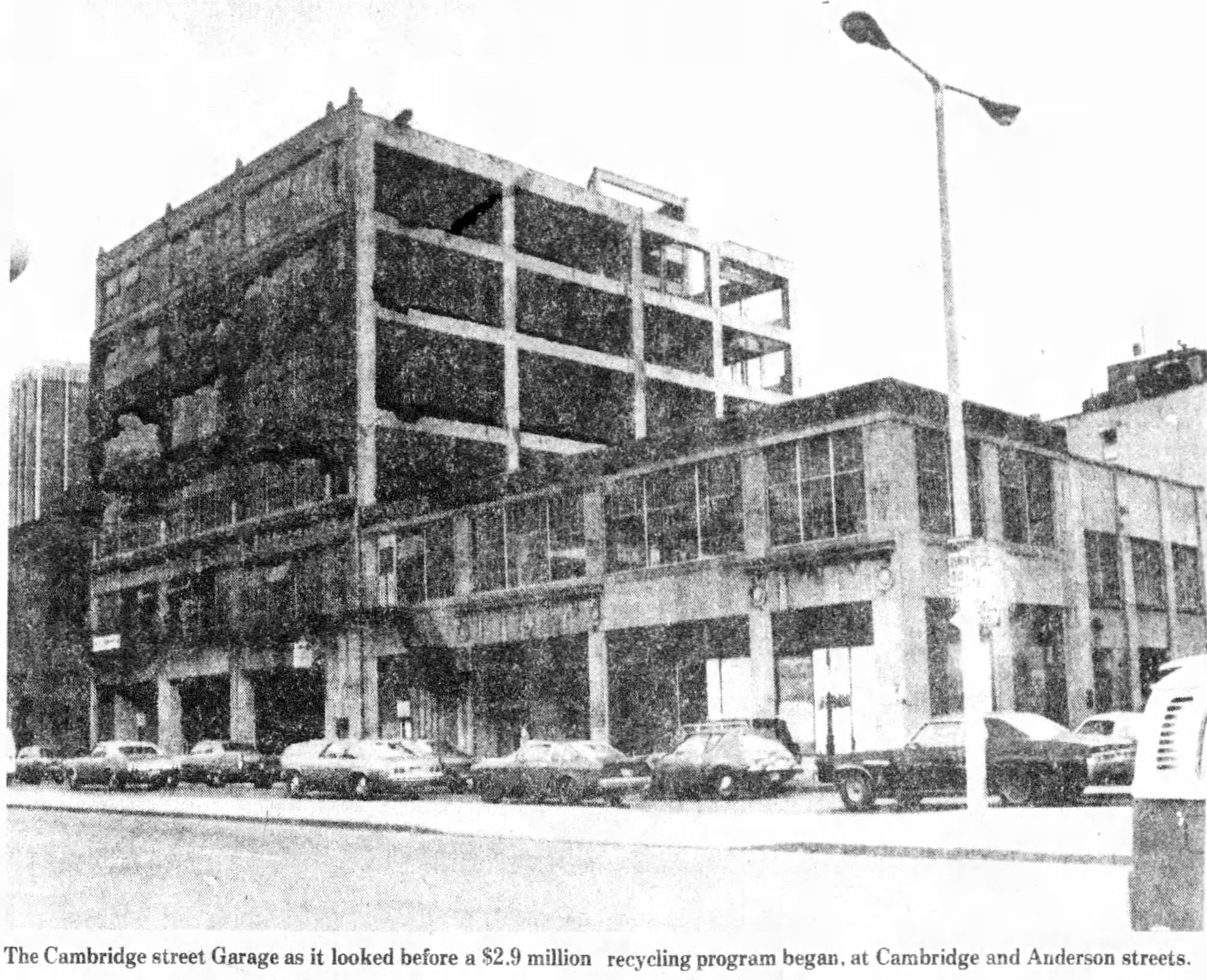

They identified a property at the corner of Anderson St and Cambridge St, which

had served for some decades as the site of a six-story parking garage. Working

with Mass General Hospital, they developed a plan to consolidate hospital

parking on the other side of the street. This would free up the Anderson St

site for a new use.

The position of the group and of the Beacon Hill Civic Association at the time, was that affordable housing should be a priority in new developments. The group therefore worked with developer Bob Kuehn to assemble a team including architectural firm Stull Associates, builder B.H. Macomber Co., and property management company Abrams Management Co. To finance the project, they obtained both 121A tax relief from the City of Boston and Section 8 rental subsidies from MHFA (now MassHousing).

As reported in the same 1979 article, the result was a mixed-use development with 6,000 sq ft of retail space, 32 one-bedroom apartments, 30 two-bedroom units, and two three-bedroom units, with 80% of the residential units having some form of subsidized assistance. The property continues to operate as affordable housing to this day, with all of the units now under contract for Section 8 subsidies.

The development and operation of single-room occupancy units without bathrooms or kitchens has been curtailed in recent decades. Although SROs were once common in US cities in the late 19th and early 20th century, Boston can learn from the examples of other cities to see how former SRO buildings can be redeveloped into apartments that meet modern expectations for privacy, safety and hygiene.

In addition to HUD funding for rehabilitation, in many locations, there is regional funding specifically allocated for this purpose. For example, New York State Governor Kathy Hochul has recently updated development guidance and allocated state $50M in state funding for the redevelopment of SROs through “preservation projects that rehabilitate SRO units to bring them into a state of good repair and add private bathrooms.”

The Downtown Women's Center in Los Angeles was founded in 1978 and pioneered the development of services dedicated to supporting women experiencing homelessness. Jill Halverson, the founder, was an outreach worker whose chance encounter and friendship with a woman named Rosa inspired her to open a facility on East Los Angeles St in July of 1978 to provide daytime services and support specifically for women.

According to a November 18, 1984 Los Angeles Times article, Downtown Women's Center quickly became “a celebrity cause in Los Angeles, attracting women in big cars and designer clothes to work among the homeless souls who live their lives out of carts and bags.” With this visibility and fundraising support, Halverson and the Downtown Women's Center were able to put together $830,000 in cash to buy a site next door on Skid Row that would open in 1986, serving as the city's first permanent supportive housing specifically for women.

Developing single-room supportive housing units was a groundbreaking idea in the 1980s, but as times changed and Downtown Women's Center grew, it must have become clear they would need a bigger space with higher-quality units. According to a December 9, 2010 Los Angeles Times article, The City of Los Angeles granted them the title to a nearby building, a vacant former shoe factory built in Gothic Revival style, on South San Pedro Street on Skid Row for $1. This new 67,000-square-foot facility opened in 2010, with 71 studio apartments that included private bathrooms and kitchens, as well as a private “rooftop garden, a daytime drop-in center and Skid Row's first medical and mental health clinic specifically for women.”

In a 2021 flyer on their supportive housing program, Downtown Women's Center explains how the private outdoor space is important to residents who “have not felt safe outdoors since first entering homelessness.” The former SRO facility that lacked private bathrooms and kitchens was shut down.

Lawson House was once the largest single-room occupancy building in the city of Chicago. According to an April 2, 2024 article in Block Club Chicago, this former YMCA building in the Gold Coast neighborhood formerly held 583 single-room apartments without bathrooms or kitchens. A renovation that completed in 2025 converted the building into 400 micro-apartments with kitchenettes and bathrooms, furnished with twin beds, drawers, and kitchen tables and chairs. A quarter of the renovated units are fully accessible, and the new development includes a private roof deck, onsite laundry, a gym, and private storage spaces.

The building at 654 Bergen Avenue in McGinley Square, in Jersey City, was built in 1924 as the home of the Jersey City YMCA. For 70 years, it operated as a 210-unit SRO building with shared bathrooms and facilities. According to a November 14, 2022 Jersey City Times article, The Community Builders purchased the historic building in 1999 and began a gradual restoration and conversion of single-room units to studios with private kitchens and bathrooms. The final round of updates will complete this year, with $81.5M in investment yielding 111 studio apartments serving as permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless residents and a new tower with 92 mixed-income apartments. Construction financing for the latest round was provided by the HUD Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) Program, with new amenities including a gym, a suite for social services, a community room, a demonstration kitchen, and a learning center.